Voice

This guide is available as a Word document or PDF.

Natural Versus Synthesized Voice

Instructors have the option of lecturing with the human voice or a computer-generated voice. In a study involving a lecture on lightning formation, students learned better from the recorded human voice than the Microsoft text-to-speech software (Atkinson et al., 2005). This finding aligns with the voice principle, which asserts that the human voice is superior to a computer-generated voice for lecturing (Fiorella & Mayer, 2021). However, improvements to voice synthesis technology have made computer-generated voices similar to or better than human voices for learning (Craig & Schroeder, 2017).

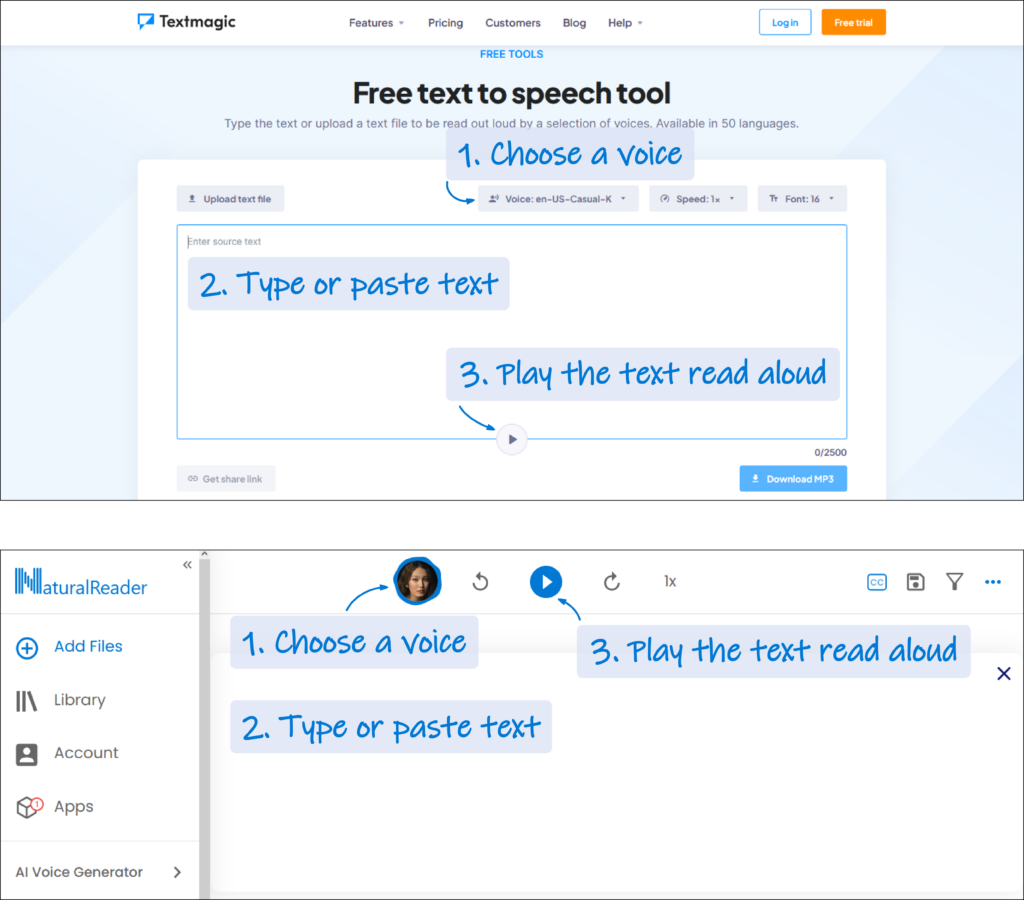

A Google search for text-to-speech applications can bring up many choices. Among these choices, Textmagic and NaturalReader came up early in the search and are free to use without logging in. To use them, select the desired voice from the dropdown menu, enter text into the text field, and press the “play” button to have the input text read aloud (Figure 1).

Even though synthetic voices have evolved from sounding robotic to more life-like, lecture content that has large amounts of heteronyms or technical words may exceed the capabilities of voice synthesizers and, thus, require the course developer’s subject matter expertise to speak these words (Table 1).

| Written input | Jonathan | “en-US-Casual-K” |

“Jane” |

| Lead(II) nitrate in water can lead to environmental hazards. | Remark: Awkward pauses when saying “lead(II) nitrate”. |

Remark: The ionic charge “(II)” is omitted. |

|

“Lead” is a heteronym.

|

|||

| The unionized group of teachers believe that the side chains of acidic amino acids are unionized below the isoelectric point. | Remark: Mispronounced heteronym. |

Remark: Mispronounced heteronym. |

|

“Unionized” is a heteronym.

|

|||

| carbocation | Remark: Mispronounced technical word. |

||

| “Carbocation”, pronounced as “carbo-cat-ion”, is a technical word in organic chemistry referring to an organic molecule with a positively charged carbon atom. | |||

| cyclooctatetraene | Remark: Mispronounced technical word. |

Remark: Mispronounced technical word. |

|

| “Cyclooctatetraene” is a cyclic molecule with alternating single and double bonds and has the formula C8H8. The word is pronounced as “cyclo-octa-tetra-een”. The “oo” and “ae” are not diphthongs. | |||

| Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc | Remark: He tries his best according to the pronunciation by Thompson Rivers University (n.d.). |

Remark: Computational difficulty. |

Remark: Computational difficulty. |

| “Tk’emlúps te Secwe̓pemc” means “the people of the confluence” and is an Indigenous group of people in British Columbia who speak Interior-Salish Secwepemc (Tk̓emlúps te Secwépemc, n.d.). | |||

Moreover, the synthesized voice may convey an emotion that does not match the spoken message, which may confuse the listener (Table 2). Also, the mismatch in emotion may make it difficult to use vocal cues to emphasize key words.

| Written input | Jonathan | “en-US-Casual-K” |

“Jane” |

| Stop them! They’re stealing my car! |

Foreign Accents

Whether lecturing with the human voice or a synthesized voice, a point to consider is the accent. One study found that lecturing in an unfamiliar accent affected learning negatively (Chan et al., 2020). In the study, college students who were native speakers of American English listened to a slideshow about lightning formation. Students learned poorly when the slideshow was narrated by someone whose native language was Cantonese and spoke with a foreign accent compared to that of an American who speaks Standard American English. The potential remedies are to display closed captioning when the lecturer speaks with a foreign accent (Chan et al., 2020) or to lecture in a synthesized voice that matches the students’ accent.

Although the study (Chan et al., 2020) provides valuable insight, it can have problematic implications. The issue of discriminatory hiring practice arises when we consider whether we should only hire instructors who speak English with a Canadian accent for the presumption of better learning.

Another interpretation of the foreign accent study is that the lecture is best delivered in a manner of speaking familiar to the students. Hence, if most of the students in a class speak a native language other than English, then perhaps we should hire instructors with a matching native, or faked, accent to maximize the numbers of students who can learn effectively. Such a resolution would seem rather awkward.

When hiring, there could be human rights issues with discriminating based on how someone speaks. Discrimination according to language proficiency may be acceptable (BC Human Rights Tribunal, n.d.). However, discriminating based on someone’s accent may be interpreted as racial discrimination (BC Human Rights Tribunal, n.d.; Ontario Human Rights Commission, 2009).

Summary

- Even though artificial intelligence has made tremendous progress in voice synthesis, the technology is imperfect.

- The human voice, rather than a synthesized voice, is preferred for lecturing.

- We all speak with some sort of accent, and speaking accent may be a contentious issue when hiring lecturers.

Media Attributions

The featured image was created by Jung-Lynn Jonathan Yang under a CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. All figures are screenshots taken and used under Fair Dealing guidelines.